Since the 1980’s Spain has been an active player when it comes to privatisations. Although not reaching the level of the UK under Margaret Thatcher’s mandate, the socialist government of Felipe González [PSOE] started selling off many of Spain’s public heirlooms from 1985 onwards. When the conservative José Maria Aznar [PP] assumed office in 1996, he picked up where his predecessor left off, by selling a staggering fifty companies worth over 30 billion euros until 2004. Although the speed of privatisations somewhat declined under the government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero [PSOE], the economic crisis was the perfect opportunity for the government of Mariano Rajoy [PP] to pick up the privatisation scheme again. Bound by agreements with the European Union to reduce the public debt, in 2012 the government came up with a plan aiming at privatising nearly all remaining public assets such as Renfe, Aena, Puertos del Estado and many local services.

Spain is not the only crisis-ridden country being pressurized into selling off its assets in order to meet deficit targets. During the economic crisis, supranational institutions such as the European Commission and the IMF have endorsed and actively promoted privatisations, making it one of the central planks in their agreements with debtor countries such as Greece, Ireland and Portugal. In 2012, the European Commission in correspondence with civil society groups, explained its explicit endorsement of privatisations as follows: “privatisation of public companies contributes to the reduction of public debt, as well as to the reduction of subsidies, other transfers or state guarantees to state-owned enterprises. It also has the potential of increasing the efficiency of companies and, by extension, the competitiveness of the economy as a whole, while attracting foreign direct investment.”

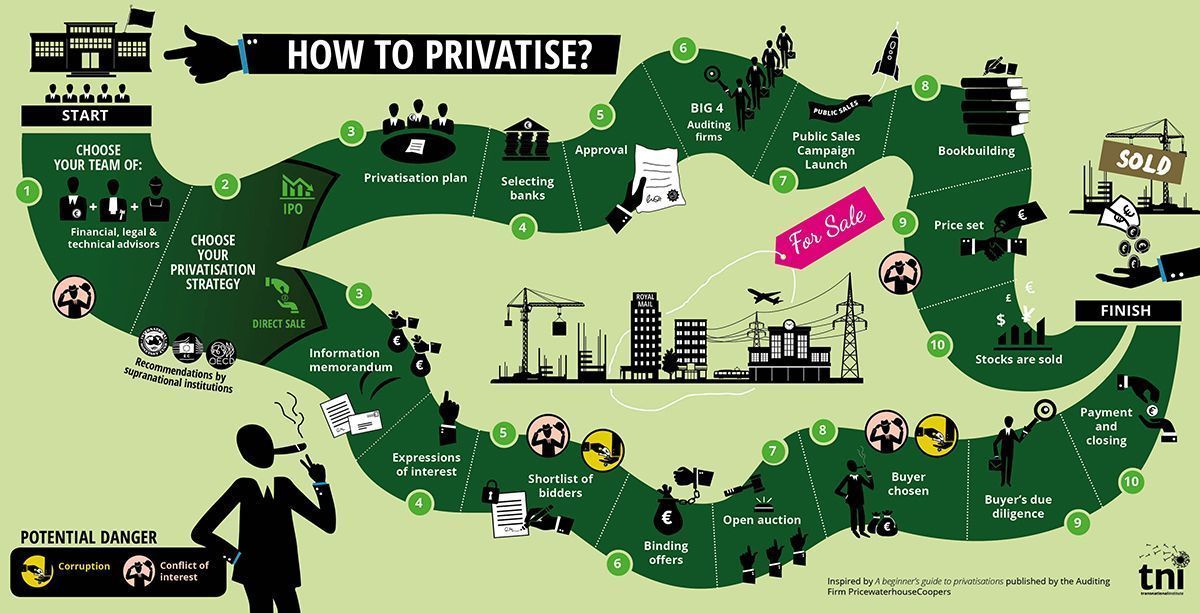

In the past years a privatising industry has formed throughout Europe, in which a couple of small corporate actors are dominating the privatisation advisory business

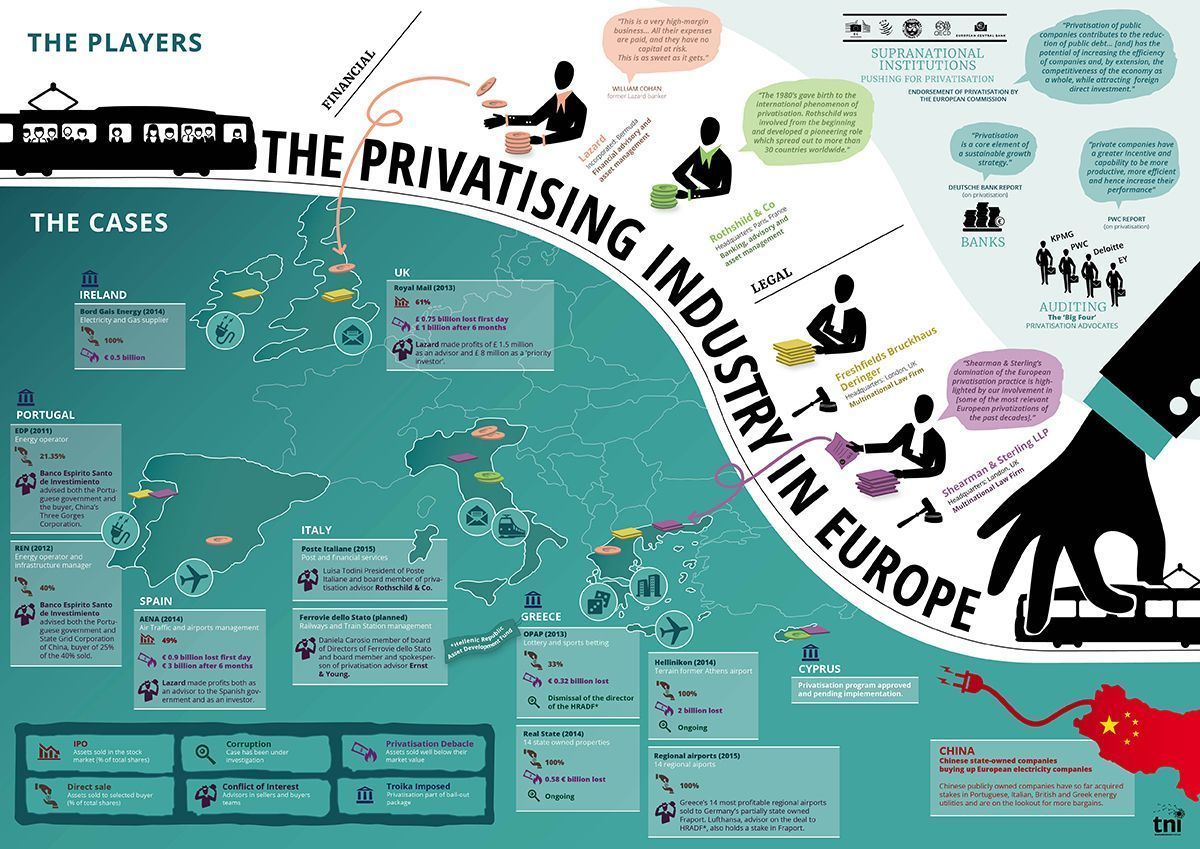

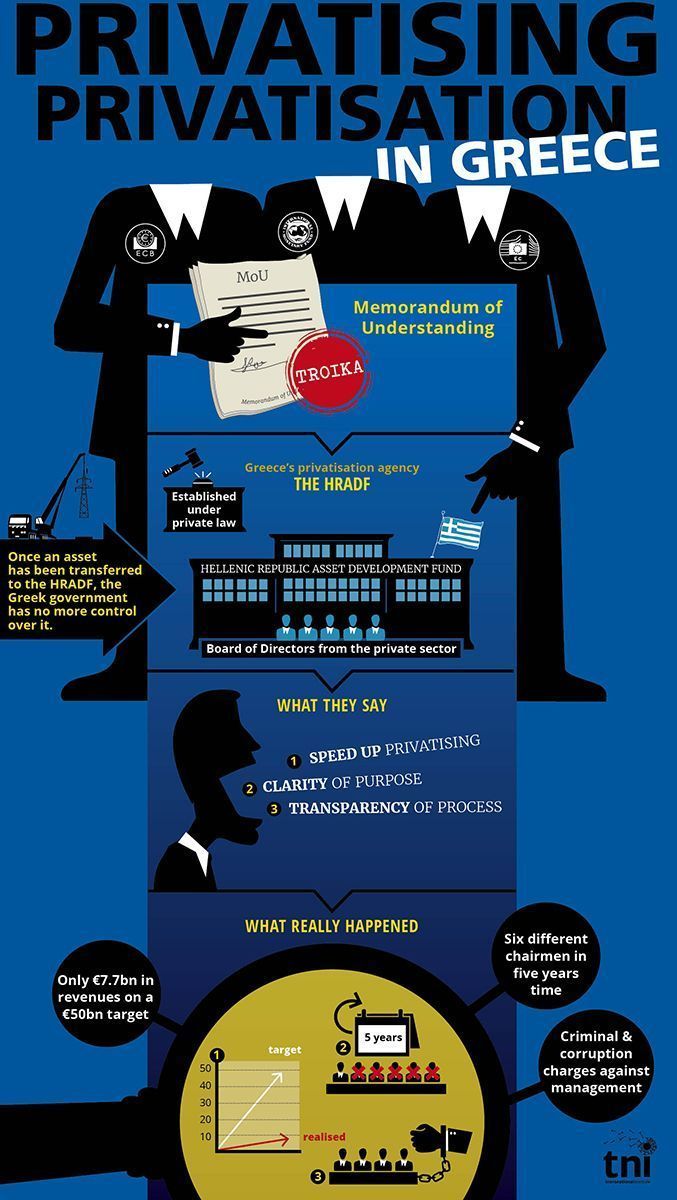

In other words, according to the European Commission, privatisation helps to reduce public debt, while making companies more efficient. However, how do these arguments stand out in practice? And which are the actors that stand to gain most from Europe’s privatisation schemes? In La industria de la privatizacion en Europa, the latest report by the Amsterdam based think tank Transnational Institute (TNI), these questions are being put to the test. The report reveals that the sale of state assets during a recession have consistently failed to meet revenue expectations. This has most notably been the case in Greece, where an extensive privatisation programme was part of the country’s deal with the Troika. Whereas the original Memorandum of Understanding foresaw a 50 billion euro target in privatisation revenues by the end of 2015, the state has so far managed to collect a measly 7.7 billion by selling some of their most profitable state assets.

Moreover, in the past years a privatising industry has formed throughout Europe, in which a couple of small corporate actors are dominating the privatisation advisory business. Furthermore, the research shows that, in the eleven high profile privatisation cases analysed, imposed far-reaching privatisation programmes often tend to lead to cases of conflicts of interest, nepotism and even corruption. This has been the case, for example, in Portugal, where Banco Espírito Santo, one of the country’s largest banks, acted first as an advisor for the state in a privatisation deal, but later switched sides and became the advisor of the Chinese state owned companies that ended up buying the assets- stakes in Portugal’s two electricity companies. While the bank was ultimately paid by both sides, the Portuguese Court of Audit calculated that the government lost out on roughly 2 billion euros on these deals. The Portuguese case is just one example out of many and the recurring pattern of conflicts of interest in privatisation schemes is a worrisome phenomenon. Unfortunately, Spain is no exception in this regard.

Infographics by TNI

One of the most exemplary cases in Spain is the IPO of Aena in 2015. One of the government’s financial advisors on this partial privatisation was the American investment bank Lazard. Lazard is a key player in Europe’s privatisation industry, having a presence in many of Europe’s major privatisations in recent years. As the financial advisor of the state, the firm played an important role in the significant undervaluation of Aena´s shares at its IPO. Due to this undervaluation, share prices rose by more than 20 percent on the first day of trading and doubled in less than two months, causing the Spanish state to potentially lose out on more than three billion euros. However, while the Spanish taxpayers were deprived of a substantial amount of money, Lazard managed to benefit significantly from this deal. Not only were they paid for their advisory services, but one of Lazard’s asset management branches, Lazard World Dividend & Income Fund, managed to obtain Aena´s shares at IPO price. The firm then sold these shares only one month later with a 60 percent profit. In other words, while Lazard advised on the price setting of Aena´s shares, the firm managed to profit of its own advice by buying up the extremely undervalued shares. A very clear conflict of interest case.

The case of Aena was not the first time Lazard managed to profit by acting on both the supply and demand side of a privatisation. Two years before, at the 2013 IPO of the British state-owned Postal giant Royal Mail, the firm had pulled off the exact same trick. Lazard was the financial advisor to the British state on this multi-billion euro IPO and advised the state in the price setting of the shares. The Royal Mail IPO was oversubscribed 24 times, causing the shares to rise by 38 percent on the first day of trading. While due to a lot of investor interest other advisors had recommended to raise the price of the shares before the IPO, Lazard had actually advised against this. While the British taxpayer was deprived of 750 million pounds on the first day of trading and potentially a lot more afterwards, Lazard actually made an 8 million pound profit by buying up shares through one of its asset management branches, which had been given a ‘priority investor’ status, and selling them off one week later. These profits came on top of their fee of 1.5 million pounds for their advisory services. When William Rucker, the Chief Executive of Lazard UK, was confronted with this obvious conflict of interest, he claimed that the ‘Chinese walls’ between the different branches of the firm had always remained intact and there had not been any exchange of information between them.

Despite the obvious conflicts of interest and the ongoing investigations, the Spanish government figured it was a good idea to keep Lazard on as their advisor for Aena’s IPO

Infographics by TNI

The Spanish government’s choice for Lazard as the main financial advisor in the giant privatisation of Aena can be considered highly peculiar. Lazard is involved in the scandal surrounding the initial IPO of the banking conglomerate Bankia, before the Spanish government nationalized it. Rodrigo Rato, former Bankia director and IMF director, is currently under investigation due to five different contracts given to Lazard during his presidency. Rato, who worked at Lazard before becoming the director of Caja Madrid, was the director of Bankia for two years until 2012. In that time he provided his ex employer with contracts worth a total of 16.4 million euros. At the same time, in 2011, Rato received 6.2 million euros from Lazard on an offshore bank account. Despite the enormous costs for Lazard’s advisory work, Bankia had to be saved shortly afterwards, in 2012, with 23,500 million euros of public money. What made this case particularly striking is the fact that Rato continued having a professional partnership with Lazard’s Spanish unit’s chairman Jaime Castellanos. While Rato initially declared he did not do business with Castellanos, his lawyer later stated they actually jointly owned a commercial lot near Madrid. Nonetheless, despite the obvious conflicts of interest and while the suspicious contracts and the payments to Rato by Lazard were being investigated by the anticorruption prosecutor (along with the investigation regarding the payments made with Bankia’s black credit cards), the Spanish government figured it was a good idea to keep Lazard on as their advisor for Aena’s IPO.

Infographics by TNI

Conflicts of interest in privatisation cases such as Aena and Royal Mail lead to heavy losses for states, although they seem to be a recurring phenomenon when national governments are forced to sell their public heirlooms in times of recession for the sake of certain rationales. The Lazard cases are no exceptions and many privatisations in Troika countries have also been subject to the same kind of nepotism and corruption, causing these states to lose out on billions of euros of potential revenue. Moreover, while one of the European Commission’s main arguments in favor of privatisation is the fact that it helps to reduce public debt, the report shows that, due to the imposed privatisation schemes, mainly the profitable state owned companies are often sold, while the unprofitable and subsidy consuming ones remain in public hands. In July 2015, for instance, the first privatisation deal to go ahead after Greece’s government signed the new Memorandum with the Troika was the sale of Greece’s fourteen most profitable regional airports, which went to Germany’s partially state-owned company Fraport. While these fourteen airports, which are all located on popular tourist islands, provided a steady annual income to the state, all the other -non profitable- airports were excluded from the deal. The sale of these airports to Fraport had been included in the new bailout deal, thus enabling Germany to be sure it would go ahead. One of the advisors to the Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund, the agency in charge of selling Greece’s assets, was Lufthansa Consulting, a subsidiary of Lufthansa, which partially owns Fraport. With Lufthansa having a vested interest in a cheap sale, the involvement of Lufthansa Consulting as an advisor to the Greek state was once again a clear conflict of interest.

The studied private companies did indeed seek to optimize cost efficiency; however, rather than by improving their technical efficiency, they tended to do this by increasing prices for consumers and lowering labour standards and wages

Through privatisations annual dividends are too often substituted for one-time payments, which, especially during times of recession, tend to be a lot lower than anticipated. This has been the case in all the examined countries; privatisation where revenue expectations were met have proven to be an exception rather than the rule.

The other argument given by the European Commission, that private companies tend to be more efficient than public ones, has also been proved of questionable veracity. The studied private companies did indeed seek to optimize cost efficiency; however, rather than by improving their technical efficiency, they tended to do this by increasing prices for consumers and lowering labour standards and wages. Ironically enough, research by a consortium of European universities funded by the EU concluded that privatisation “promoted a model of competition that is largely based on the reduction of wage costs and not on the improvement of quality and innovation.” Moreover, research by the IMF and the World Bank, two of the biggest supranational advocates of privatisation, concluded that there is no real evidence pointing to the increased efficiency of private ownership over public:

“When [outsourcing, privatisation or] Public-private partnerships (PPPs) result in private borrowing being substituted for government borrowing, financing costs will in most cases rise. Then the key issue is whether [outsourcing, privatisation or] PPPs result in efficiency gains that more than offset higher private sector borrowing costs […]. Much of the case for [outsourcing, privatisation or] PPPs rests on the relative efficiency of the private sector. While there is an extensive literature on this subject, the theory is ambiguous and the empirical evidence is mixed […]. It cannot be taken for granted that [outsourcing, privatisation or] PPPs are more efficient than public investment and government supply of services…”

Despite these conclusions, both institutions keep vigorously advocating this measure. While it is clear there is a deeply rooted economic rationale at the base of these arguments, it also seems that certain big corporate actors are actively involved in promoting a pro-privatisation tendency in order to profit from it themselves. As La Industria de la Privatizacion en Europa shows, private actors such as financial advisors, banks, the ‘Big Four’ accountancy firms and certain legal agents actively endorse and lobby for privatisation and pro-liberalization measures, both on the national and on the European level. While the future of Spain’s privatisation plans remain uncertain depending on the outcome of the next elections, the pro-privatisation lobby will undoubtedly keep pushing for the sale of public assets by future governments. It remains to be seen how the influence of advisors will influence the outcome of privatisations in the future and how the state’s treasury will be affected.