Are we ‘walking the talk’ for women in the fight to end hunger?

On the 8th March, world leaders made noble statements about gender inequality and celebrated the role of women in society to honour international women’s day (Obama, Hollande, Modi and Trudeau, among others). The same month, the UN Commission on the Status of Women concluded its 60th session. Members of this Commission committed to «the integration of a gender perspective into economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development» in the post-2015 agenda in their Political Declaration.

This means that all efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – 17 goals aiming for more inclusive, egalitarian, and prosperous societies worldwide – by 2030 should consider the impact of their efforts on women’s empowerment and gender equality. In the second goal, SDG 2, countries agreed to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture” by 2030.

To eradicate hunger we need to invest in women

This first year of the new SDG agenda centers on accountability: the SDGs should be reviewed and followed up on over the next 15 years to ensure impact where it is needed most. SDG 2 is an ambitious goal but there is evidence to suggest that it is achievable. To eradicate hunger we need to invest in women, and carefully monitor these commitments and hold the key stakeholders accountable for ‘walking the talk’, and transforming these investments into impact.

Investing in gender equality to end hunger isn’t just about feeding women, but also means healthier children and more productive farms

Benefits from investing in women to end hunger tend to extend to children and communities. Malnutrition suffered early in life can result in physical and mental damage, ultimately leading to increased susceptibility to sickness, and lost earning potential in the future. A healthier pregnant woman helps ensure a healthy baby at birth and women tend to prioritize nutrition for children more than men. Estimates attribute a 55 % global reduction in child malnutrition between 1970 and 1995 to improvements in women’s status, 43 % of which was explained by progress in women’s education.

Additionally, women are disproportionally affected by hunger compared to men. Social structures often mean women eat last and least, and they tend to sacrifice their nutritional needs for those of their family members. Furthermore, one of the most important contributing factors to the global burden of disease is more prevalent in women than men: 500 million women around the world are affected by anemia (typically a micronutrient deficiency that can lead to ill-health, premature death and lost earnings). In Africa alone, this deficiency results in 20 % of maternal deaths.

Because of discrimination and cultural norms denying women equal access to land or production inputs, financial services, and education, women also tend to be less economically productive than men. Yet, improving women’s productivity could increase agricultural output by up to 4 % in developing countries, and undernourishment could be decreased by more than 15 % in Sub-Saharan Africa alone.

Commitments need to be sustained and translated into impact for the most vulnerable

Finally, because millions of women in developing countries are missing in the data, making evidence-informed decisions is a tricky task. Organisations like Data2X argue that in order to be actionable, data are needed to “describe the unique circumstance of the population, broken down by sex” and are working towards filling the data gaps on women. In good news, they recently highlighted 16 SDG-related gender indicators that are ‘ready to measure’.

Tracking donor aid to end hunger: Are donors walking the gender talk?

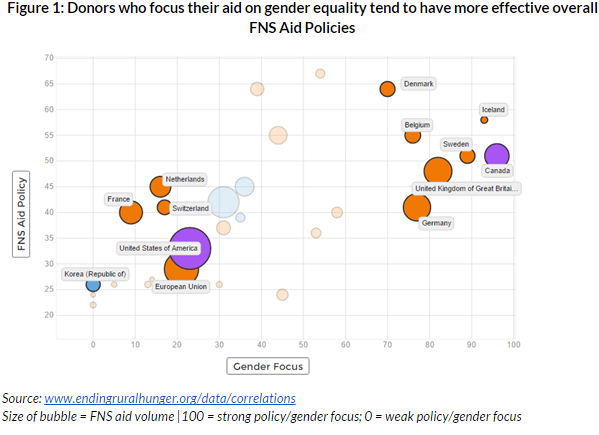

One way of holding donors accountable for the gender focus of their investments to end hunger is by looking at their aid behaviour. The OECD developed a ‘Gender Marker’ which tracks aid in support of gender equality and women’s rights [1]. The Ending Rural Hunger (ERH) project uses this marker to assess the gender sensitivity of the DAC (Development Assistance Committee) donors’ aid to Food and Nutrition Security (FNS) over 2009 – 2013 [2]. The ERH framework uses this indicator to help determine the quality of a country’s FNS policy based on international aid effectiveness principles.

Figure 1 correlates countries which have a strong focus on women in their FNS investments (towards the right), with countries which have a strong overall FNS policy [3] (towards the top). It shows a positive correlation between a strong focus on women in FNS aid investments and more effective FNS aid policies.

Are donors investing in gender-sensitive aid for nutrition and agricultural productivity?

SDG 2 attributes special attention to women when it comes to malnutrition and agricultural productivity [4]. Individuals need diverse and healthy diets so they can lead productive, active lifestyles and achieve their full potential. Productive agricultural systems are necessary to ensure the availability of food for their households, communities, and countries. Agricultural productivity is also a powerful tool for lifting people out of hunger as it can help raise the income of family farmers and off-farm rural wages, and reduce local food prices.

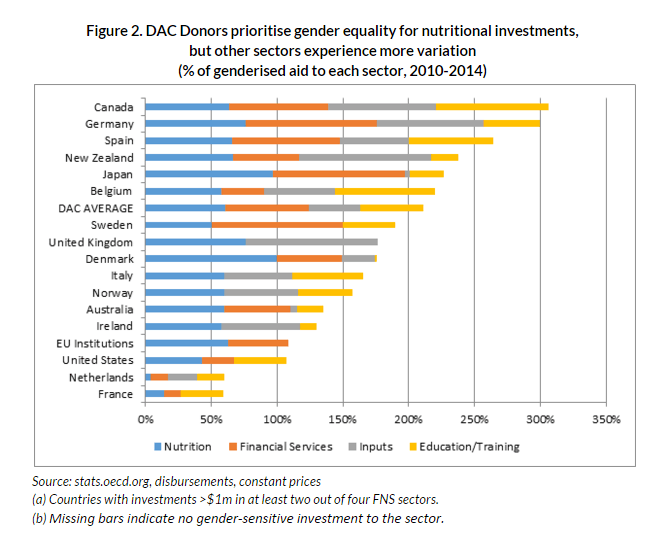

Going one step further in the analysis allows us to look at whether donors are targeting women in these sectors. To get a sense of gender-sensitive nutrition investments, activities reported as basic nutrition are considered. Agricultural financial services, agricultural inputs, and agricultural education/training [5] are some of the key components allowing farmers to be productive, and are thus considered in the below analysis.

On an aggregate level, DAC donors appear to be taking gender equality seriously in the fight to end hunger. The average gender focused portion of all DAC aid investments over 2010-2014[6] was just 28 %, compared to 63 % for financial services, 61 % for nutrition, 48 % for agricultural training and education, and 39 % for agricultural inputs.

The only DAC donors with less than half of their nutrition investments focused on women were the Netherlands (4 %), France (14 %), and the US (43 %). Other FNS sectors experience more variation but overall, interventions supplying key inputs such as seed and fertilizer, are least focused on women.

Canada and the US are major FNS donors, both in terms of volume and in terms of political leadership on hunger and gender inequality issues (Obama, 2016; Harper, 2014). Based on the available data, Canada appears to be transforming words to action, while the US is falling short.

Canada accounts for 6.2 % of DAC aid to FNS between 2009-2013. One of Canada’s three core priority areas is maternal, newborn, and child health, and their cross-cutting priorities include ‘empowerment of women and girls’. In 2010, Canada launched the Muskoka Initiative to accelerate progress in maternal and child nutrition, aiming to prevent the deaths of 1.3 million children and 64,000 maternal deaths. Following through on these commitments, they have been investing heavily and consistently in women, across all sectors. Further, Canada tends to report their FNS and gender investments with great detail, pointing to a genuine will for transparency.

The US accounts for more than 22 % of all DAC aid to FNS between 2009-2013. In 2012, under the US G8 Presidency, President Obama launched the New Alliance for Food and Nutrition Security, cementing their leadership in the fight to end global hunger. The US’ flagship programme, Feed the Future, prioritises ‘gender integration’ as one of 6 key focus areas, and specifically aims to improve child nutrition in the 1000 day window starting from pregnancy.

Yet none of their agricultural input investments were focused on women, and the US is one of just three countries investing less than 50 % of their investments to nutrition on women.

The hunger community is at risk of ‘putting women to work for development’ rather than figuring out what development can do for women

Conclusion

Although achieving the end of hunger by 2030 is a monumental task, there are signs of genuine political will and actions taking place that allow us to hope for success. We know we need to change the business as usual approach: commitments need to be sustained and translated into impact for the most vulnerable.

Most countries in the world will agree that considering the impact of policies on both men and women is imperative to their success. DAC donors are involved in numerous global agreements and when it’s timely, they can be heard passionately pushing for women’s rights and gender equality. But it’s important that we hold our governments accountable for translating these words into action.

Overall, this brief analysis is a good news story: although there are clear variations between donors, overall, large amounts of FNS investments from DAC donors are being invested with a ‘gender lens’. The specific sectors looked at (nutrition and agricultural productivity) are especially focused on gender, even if investments to the more ‘production-oriented’ activities (agricultural inputs) still tend to be less focused on women.

Throughout this analysis, it also becomes evident that the hunger community is at risk of ‘putting women to work for development’ rather than figuring out what development can do for women. When investments are made in women’s agency, we need to be cautious of the triple burden which imposes more work and less time on women as they gain employment, but maintain their traditional roles of childcare and housemakers.

[1]^The gender equality policy marker is based on a three-point scoring system:Principal (marked 2) means that gender equality is the main objective of the activity. Significant (marked 1) means that gender equality is an important but secondary objective. Not targeted (marked 0) means that the activity does not target gender equality.

[2]^This was the latest available data at the time of analysis. The database will be updated later this year with 2014 data.

[3]^Defined in ERH as policies that focus on gender, climate change and broader aid effectiveness principles such as aid that is less volatile and fragmented.

[4]^“Target 2.2: By 2030 end all forms of malnutrition, […] and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women” and “Target 2.3: By 2030 double the agricultural productivity and the incomes of small-scale food producers, particularly women”.

[5]^Based on the OECD list of CRS purpose codes.

[6]^Latest available data.