Anupama Kundoo (1967, Pune, India) participates for the second time in the Venice Architecture Biennale, this time directed by the recent Pritzker Prize Alejandro Aravena. Under the title Reporting from the Front, Aravena intends to showcase how architecture confronts the growing problems of urbanization and the contemporary challenges of society such as inequality, mass migration and climate change. These are issues that Kundoo, now based in Madrid, has been dealing for more than two decades of international practice.

The Biennale, after many years of promoting the star-system in architecture, has finally put an emphasis in the architecture of the other 99 %. The title given by Aravena seems to present the world’s inequalities and environmental issues as a new battle for architects. However, this battle has been going on for a long time in a lot of places. How do you see this change of paradigms?

I think it was mostly the media who first created certain icons, coined this term, and those who are now questioning it —although this is mostly a discussion in the Eurocentric world. I don’t think that the rest of the world is worrying about such a star-system. There is nothing wrong with idealizing people, with calling someone a master or a guru when it’s someone who inspires others. I have no problem with that. The pertinent question here is to ask ourselves who and what we are glorifying.

For some time, the architectural (incestuous) circle itself got overly impressed by the spectacular and the iconic, disregarding other precious architectural values. Advances in digital technologies have transformed the way architects produce drawings, now exclusively on computers, and so there was this wave of excitement about generating all sorts of forms even often at the cost of other timeless qualities that form the basis of good architecture. The media has admired and helped in promoting such photogenic architectural images and neglected other aspects that architects have been addressing for generations. Architects have to know about urban issues, they have to know context, they have to know engineering, construction, details as well as climatic strategies, environmental and territorial impact: the capacity to achieve a synthesis of all these concerns through a holistic design, this is what good architects deliver. There has been a fascination with certain aspects of novelty or fashion, but those things never last.

I have been subject to different labels: first the green architect, then the contemporary vernacular architect, then the social architect, now I am the woman architect… But this is not serious

Portrait of Anupama Kundoo at the Biennale’s Arsenale. Photo: Marta San Vicente

Once this is overdone and the fashion is passé, as the trends are no longer convincing, there is unfortunately the natural tendency of the pendulum to swing to the other extreme. One has to be careful not to fall into this trap. Rather than finding a balanced view, after overrating something, there could be an over-idealisation of the opposite. This looks like a shift, but this is deceiving as it’s exactly the same tendency, now looking for new icons to personify the opposite issues that have been undervalued. It is only a process of substituting idols, and continuing to be seduced with photogenic architecture, despite their falling short in providing real lasting solutions. There is no need to sensationalize things. One could be looking in the same superficial gaze and create new «isms». There are already critical voices of this new trend, associating it with the «fetishizing of poverty architecture» to quote from the title of Dan Hancox’s piece for the Architectural Review, or more recently Toma Berlanda’s ‘media attention overload’.

I myself have also been subject to different labels according to changing fashion and obsessions: first the green architect, then the contemporary vernacular architect, then the social architect, now I am the woman architect… But this is not serious, my work has been a continuous research over the last 25 years, and I think it is enough to simply call me an architect, which in my opinion implies the synthesis of all those concerns.

I think its time to look beyond such trends, at the big picture of the rapidly urbanising planet and all the environmental, social and economic imbalances that such unprecedented global phenomenon of urban migration involve, and collect wise ideas to steer urban development and architecture. I didn’t expect from this Biennale to provide answers to all of this, but instead —like each Biennale— to share work and exchange ideas.

Population explosion calls for densifying urban areas and conserving agricultural land. Technologies that can enable this, with low environmental impact are the need of the hour

I come from India, I do not want to sell a romantic icon of architecture for the poor, the «let ́s go back to nature thing» with coconut thatch huts and so on. This has a photogenic aesthetic appeal seen from the perspective of developed countries, but it cannot be a real architectural solution for extreme situations, like the megacities where density and prevention of urban sprawl is key. I have nothing against the thatch hut itself, having designed one and inhabited it for over 10 years, but this is not the solution for those areas where real housing shortage and urban poverty exists. Apart from this there are fire hazards, and health problems relating to the fungus that breeds there, and I am not blind to those shortcomings either. What I am saying is that such a romantic idealization maybe irrelevant in the context of real needs. I prefer to propose thatch huts for the rich boutique tourist, or those who can afford to be that ecological, but give sturdy solutions to those who are so poor that need their lives savings to actually provide them some security and stability. Population explosion calls for densifying urban areas and conserving agricultural land. Technologies that can enable this, with low environmental impact are the need of the hour.

I have ideals, I think many people have, but one has to take action and be involved, and not remain aloof

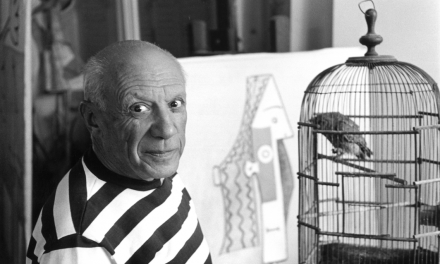

Between the columns of the Venice Arsenale, the prototypes Full Fill Home and Easy WC. Photo: Javier Callejas

Your career has been going a long way in India, a country specially threatened by issues such as urbanization, urban-rural migration or climate change. How do you consider a big scale change could be achieved? Would you defend the institutionalization of your practice?

As an architect, or any other profession, you are a member of society, a citizen; you can decide to be indifferent or to be involved, and then you can use your imagination to solve issues. I have ideals, I think many people have, but one has to take action and be involved, and not remain aloof. However, in architecture, and in front of those big scale problems, I do not think solutions are directly scalable. You cannot come and reproduce an individual project that is an investigation in itself thousands of times, because that is not an adequate solution. Every household is different, and the ways of living vary enormously. Housing is for me the most important part of architecture: it is the space between the individual and the collective, including both. And when you bring these together, all that makes architecture complex appears: public space, society, economy, environment etc.

We cannot be apathetic to the problem of huge urbanization, so the knowledge of this big picture must inform the small picture. You have to make the adequate choice so that the small work you do becomes part of a bigger whole. In our era, the challenge is huge. But we cannot come with a few people’s fetishes and personal anxieties to solve the big problem. That is why I did not expect too much from the Biennale, because one cannot consider that some strategies and concepts can solve such complex issues. The biennale is not the platform for that.

The main problem is that the new tools are substituting the traditional and necessary knowledge of the architect, instead of complementing them, and this cannot be called a progress

The piece Full Fill Home as seen from the inside. Photo: Javier Callejas

Your practice builds up on the concept of knowledge, something you literally materialized from the metaphorical in workshops such as the one during Fundación ICO’s exhibition The architect is present, or during this year’s Biennale with international students. To what extent do you consider that architectural education really manages to transmit this knowledge on thinking and building? Or has it instead been substituted by a world of visual effects, or, what could be worse, a false staging of sharing knowledge?

The main problem is that the new tools are substituting the traditional and necessary knowledge of the architect (the climatic design, the technical concepts, even how to draw), instead of complementing them, and this cannot be called a progress.

The urbanization problem is growing, so we need more knowledge to solve it. The knowledge particular to architects is needed more than ever, and even needs to be considerably enhanced. However, we are in a prison that we made ourselves. Architects now have neither the old nor the new knowledge, because the new is so complex that we only understand very little of it. The trend is to be passively using software designed by a few, and then everyone is suddenly subjected to the limitations of the software. Yes, these digital technologies and such advances have enabled a lot, but their limitations are not to be under-estimated either. Few people now have a deeper knowledge and the masses have forgotten the basic principles, they even confuse information with knowledge. It is a time to recall the knowledge we had, while building new knowledge, to release us from the limitations of our own discipline.

We need to build knowledge across disciplines too. That is why for the Biennale installation we had inter-disciplinary and inter-cultural collaborations: engineers from TU Berlin Germany, the Rebiennale activists supporting their initiative for homeless people from the outskirts of Venice, making models with the students from IUAV Venice and incorporating the UCJC Madrid students in designing its afterlife. Building knowledge takes longer, (and may not be the most efficient way to build projects), but makes you richer: now, after 25 years of practice, I see how this approach has paid off. The more I can understand, the more I can synthesize.

[This video shows the building process of the installation at Venice]

Your installation in the Biennale is organized around «Spirit» and «Matter», two opposed concepts that, precisely through their confrontation, result in new strategies and ideas. How would you describe your installation and what do you intend to transmit through it?

When Alejandro Aravena made the call, I proposed Building Knowledge as a strategy to avoid the battle [present in this Biennale’s title, Reporting from the Front]. Growing knowledge and consciousness help to integrate the existing dualities. That is because there is duality in the world, and if they work together then there is enrichment and progress. If they are in conflict, there is destruction. We have to take the best from both parts. This is the strategy I have proposed for the battle-related theme. Without duality there can be no creation. We must develop the knowledge and capacity to see the conflicting aspects as part of the whole. One may not have the solution, but perhaps the strategies to find the solution. Everyone has something to contribute.

Full Fill Home is an example of how to achieve the space needed to live, using significantly resources, with the lowest negative impact

Architecture’s essence is the void, but the void is held by material. The dualities are the material and the space; the materiality and tectonic aspects vs. the spatial aspects. Right now we are using the room, not the wall itself. That is where the utility of architecture lies. But given the current context of environmental, social and economic impact of current building trends, our full-scale prototype of a ferrocement prefabricated home, called Full Fill Home, is an example of how to achieve the space needed to live, using significantly less resources, with the lowest negative impact. The storage space is also built-in as smaller voids within the ferrocement elements that are the building blocks. There is no not need to buy furniture, that also occupies space, but they can just move in. This is a minimalistic approach like in the times of the early modernism, where the essence defines a new aesthetic, rather than the architecture representing the struggle and shortage or poverty. Rather the architecture being composed of the absolute essentials, a synthesis of engineering and architecture is stripped off all superfluous, revealing a timeless beauty, harmony and order that is made up of the actual balance of the different aspects coming together precisely.

Ferrocement is a very thin version of concrete, 25 mm thick, but reinforced by finely distributed steel mesh instead of heavy steel bars. But this is not about traditional materials vs new materials; it is about using knowledge to make the same quantities of material go a longer way. Building many more square meters with significantly less resources. That is the progress.

On one side of the installation you see the finished architecture, while on the other side you see the unfinished elements of investigations, where the processes are revealed

Models made by IUAV students of the Volontariat Home for Homeless Children in India. Photo: Javier Callejas.

To emphasize this idea of duality, we arranged our archival material, as an inventory of strategies, on either side of the full-scale Full Fill Home prototype and Easy WC. On one side we arranged the spatial research undertaken (through 1:50 scale models produced by IUAV in a workshop), and on the other side we had tables showing our material research and samples grouped on 6 tables. To support these material investigations, there are monitors with film chapters showing processes and people involved in these developments. The central piece represents this synthesis, bringing together research and design of materials, technologies, engineering, space, lifestyle, economy and other concerns. So on one side you see the finished architecture, and the quality of spaces, while on the other side you see the materiality, and the unfinished elements of investigations, where the processes are revealed.

Tables with research material and audiovisual pieces where the construction processes are shown. Photo: Javier Callejas.

Technology allows us to get more knowledge, but information itself is not knowledge, it needs to be filtered and digested to become knowledge

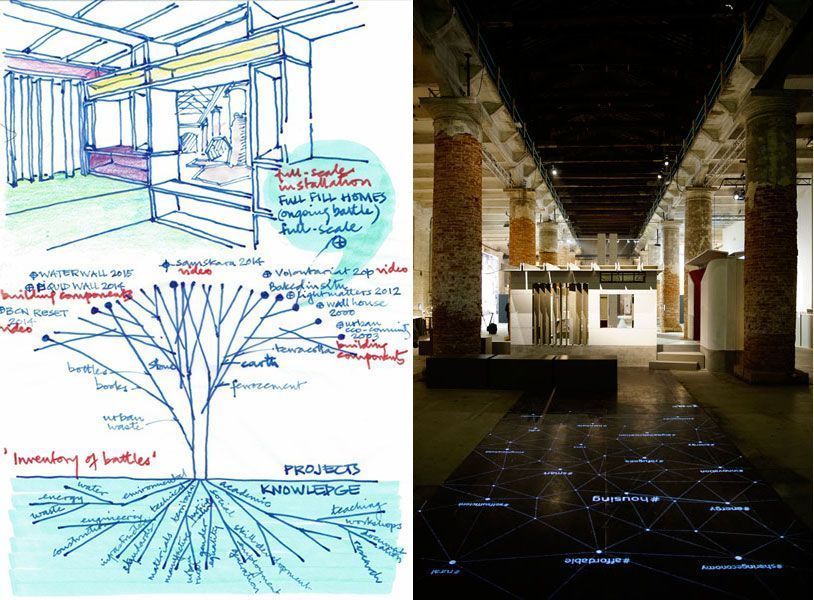

Also, there is a projection on the ground made in collaboration with IAAC [Institute of Advanced Architecture of Catalonia], with whom I have collaborated before. It is a projection of live tweets on the ground, called Live Knowledge, and where a series of hashtags related to this topic of affordable habitat is shown real time. This is the real inclusive aspect, demonstrating that everyone has something to contribute, and we need to hear others, and today we have the technology that enables us to do so. Everyone everywhere can be part of this discussion through Twitter, as we facilitate that people in the world can help build knowledge and interact with the installation. This is for me a very good example of taking advantage of technological advances, but sometimes technology is misused by remaining in its own bubble, forgetting what architecture really is about: people. Technology allows us to get more knowledge, but information itself is not knowledge, it needs to be filtered and digested to become knowledge.

LEFT: Drawing by Anupama Kundoo to explain metaphorically that the roots are the knowledge and the fruits are the outcome projects. RIGHT: Interactive installation ‘Live Knowledge’ by IAAC. Photo: Javier Callejas

In Spain, students divide their learning process between the home and the University. I prefer the American studio culture. But Spaniards have a very good general level of traditional skills, especially of drawing

Finally, having lived and taught in Spain for some years now, what are in your opinion the main issues in Spanish architectural education and do you consider Spanish architects are facing them consequently?

I find it very positive that Spanish students and architects have a spontaneous understanding not only of the house, but of the urban context, of urban design, coming from the collective memory of having grown up in liveable cities. Living outdoors being a very essential part of the Mediterranean life, public space withstood the interventions caused by the private automobile unlike in many other countries where architects are producing objects that don’t connect with the urban context and even the immediate neighbouring adjacencies. Having taught at different institutions in different countries (TU Berlin, AA London, Parsons, Brisbane, UCJC Madrid, Cornell, ETSAB, etc.), and having interacted with many others, I do often reflect on the studio culture and the ways that architecture is taught globally. I do see the advantage of the studio culture in the American Universities, which I think is optimal and conducive to teaching design, where each student gets a studio place to develop her/his personal work. This is lacking in Spain, where students here have to carry models back and forth and they divide their learning process between the home where the produce the work, and the University where they receive feedback. I prefer the studio culture.

In Spain there is a very good general level of traditional knowledge and skills, especially of drawing. Architectural education also involves the development of dualities, being the intersection between art and the physical realities: the physics, the engineering, and the construction. In architectural education we need to develop skills and knowledge but also imagination. But perhaps the system is a bit too inward looking. But in todays times, we need to be more open to global concerns. Even if the practice is not going to be global, the local practice doesn’t need to be well informed of the global concerns and rapid transformations. Surely many more Spanish architects are teaching abroad in the culturally diverse foreign universities, compared to the number of foreign teachers inside the Spanish academic institutions. The system doesn’t seem to be open to this, as one finds in other European universities. In this sense it seems a bit conservative in general. Also Spanish architects work in a more or less similar way, there is more uniformity than individual identity and uniqueness. Perhaps some cross-pollination with other cultures of design teaching could be enriching, and through interactions with others from outside this system, perhaps students could become more aware of their uniqueness as individuals and develop this uniqueness better.

In any case I see that there is a very strong and active architecture culture in Spain, it is a topic that is discussed publicly even by the layman. People in general seem to be conscious of the relevance of architecture, respect design and take pride in their city’s buildings. There is so much discussion and activity around design and architecture here and that’s what matters.

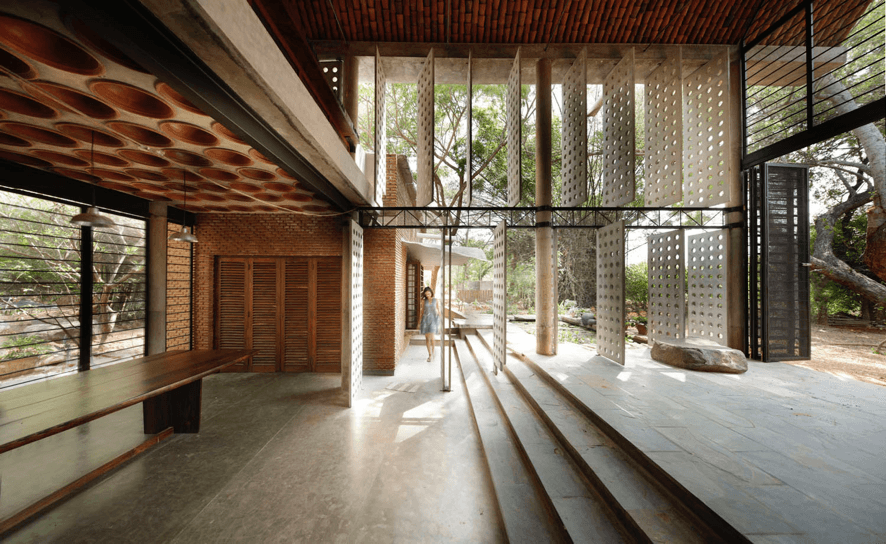

Wall House in Auroville, India. Javier Callejas